For sheer all-round entertainment, there are few films which can top

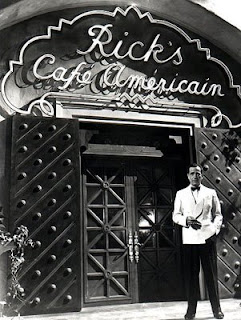

As the old saying goes, it's better to have loved and lost than not to have loved at all, and that's exactly the thing about Rick Blaine. A man jilted at a station platform in Paris during its darkest hour (German occupation in 1940), he has wound up together with his loyal bar room singer Sam (Dooley Wilson) in the ramshackle cosmopolitan city of Casablanca, with his own highly successful nightclub, which is a bevy of hopeful asylum seekers (as they would be called nowadays) hoping to escape the Nazis from the French collaborators in Morocco, to get to the United States. To do that, they need exit visas to get to Lisbon. To get visas, most of them need to use the black market, most of whom meet at Rick's. As Captain Renault (Claude Rains) explains, "everybody comes to Rick's."

As the old saying goes, it's better to have loved and lost than not to have loved at all, and that's exactly the thing about Rick Blaine. A man jilted at a station platform in Paris during its darkest hour (German occupation in 1940), he has wound up together with his loyal bar room singer Sam (Dooley Wilson) in the ramshackle cosmopolitan city of Casablanca, with his own highly successful nightclub, which is a bevy of hopeful asylum seekers (as they would be called nowadays) hoping to escape the Nazis from the French collaborators in Morocco, to get to the United States. To do that, they need exit visas to get to Lisbon. To get visas, most of them need to use the black market, most of whom meet at Rick's. As Captain Renault (Claude Rains) explains, "everybody comes to Rick's."

Everybody Comes to Rick's was the very title of an obscure stage play on which Casablanca was based, brilliantly adapted by the Epstein brothers and Howard Koch (with the added subtle creative input of producer Hal Wallis) into a film which was ultimately much greater than the sum of its parts, a glorious contradiction of the auteur theory and proof positive that, sometimes, when a studio film involves the collaboration of several talented people, the result is cinematic gold.

As often seems the case with classic films, certain legends and myths have cropped up about its making: for instance, early publicity stated that the leads were going to be Ronald Reagan and Ann Sheridan - Reagan at the time was a likeable leading man, usually to be found in the supporting role in a major Warners Brothers' feature; Sheridan likewise was an emerging new star at the Warner studio, but the truth is that this was just a bit of studio publicity intended to engender interest in the film.

From the outset, there was only ever one choice for Rick and that was Humphrey Bogart. Having stuck around at Warners for so long as semi-protagonists or shady adversaries for the likes of James Cagney and Edward G. Robinson, Bogart's career had suddenly gone into fifth gear with The Maltese Falcon, and suddenly (thanks to John Huston) the studio had a figure of world-weary cynicism that somehow perfectly suited the atmosphere of 1940s, and the role of Rick Blaine was tailor-made to suit him and his admittedly slightly limited but malleable acting range.

The reason why Rick is so embittered with the world around him becomes all too apparent when that reason just happens to wander into his nightclub , in the shape of the beautiful Ingrid Bergman as Ilse Lund.

"Of all the gin joint in all the towns in all the world, she walks into mine."

There were other glamorous ladies considered for this leading role, and I daresay those who've played this sort of role in the years since, but none of them could have struck the right balance as Ms. Bergman. Her apple-faced beauty combined with a winning smile and a certain inbred Scandinavian conviction were perfect for playing a woman that would easily steal the heart of Rick Blaine. As Captain Renault (Claude Rains again, who has all the best lines) so aptly puts it:

beauty combined with a winning smile and a certain inbred Scandinavian conviction were perfect for playing a woman that would easily steal the heart of Rick Blaine. As Captain Renault (Claude Rains again, who has all the best lines) so aptly puts it:

"I was informed you were the most beautiful woman ever to visit Casablanca. That was a gross understatement."

At Ilse's side, to Rick's further surprise, is eminent anti-Nazi Victor Laszlo, as played by Paul Henreid, who had recently become a heartthrob of sorts opposite Bette Davis in Now, Voyager, so he seemed an ideal choice for the third part of this love triangle - a tough role to play, as most female eyes were automatically turned towards Bogart.

An added irony to the casting of Paul Henreid was that for a time he was actually suspected of

pro-Nazi sympathies (being Austrian) when he first came to America - something which friends and colleagues in the British films he had been working in quickly dispelled - whereas Conrad Veidt (as the smooth chief Nazi Major Strasser)

was actually a refugee from Nazi Germany. In the movies however, the two stand-off each against other as very different sides of the same coin.

Which way Ilse chooses to turn (Rick or Victor) is pretty well known by now, so I won't bore the reader with plot details, and save those that haven't seen the film to enjoy it unravel for themselves. The thwarted love of Casablanca (as too in Brief Encounter) is the fundamental reason for its classic status, but what's less celebrated is the tremendous range of ensemble characters. It seems to add to its power that some of those gathered within Rick's "Cafe Americain" were actual refugees from the Nazis, such as Helmut Dantine (as a young Bulgarian newlywed), himself another fervent Austrian anti-Nazi; ironically, in Operation Crossbow years later he played the ruthless commanding officer at the German rocket base in Peenemunde, taking over from his predecessor played by: Paul Henreid!

The Warner studio itself had politically gone out on a limb by speaking out openly against Hitler with Confessions of a Nazi Spy in 1939 - two years before the US entered the war - and they also took on a wide range of European emigres who had forcibly fled the Nazis in the 1930's, more than any other major studio. So the Warner "stock company" at the time included a whole bunch of European actors such as the ever-likeable S.Z. "Cuddles" Sakal as chief waiter Carl, Leonid Kinskey as flirtatious barman Sascha, a great comedy cameo by Curt Bois as a smooth-talking pickpocket, and of course, two of Bogart's co-stars from The Maltese Falcon, Peter Lorre and Sidney Greenstreet - the latter having just become a star in his debut film (at the age of 60), and whose cameo as Signor Ferrari in Casablanca is fleeting, but like the good actor he is, he relishes every scene.

There was also Marcel Dalio - as Rick's smooth-talking croupier - who had fled his native France where he'd been a star of such notable films as La Grande Illusion and La Regle du Jeu. Come the German invasion of Western Europe however, Dalio was branded "the quintessential face of a Jew" and French Cinema's huge loss

was undoubtedly Hollywood's gain; in the scene where Dalio's wife, actress Madeleine LeBeau (who plays the disillusioned Yvonne, a rejected ex-lover of Rick's) sings La Marseillaise in the Cafe to a rousing chorus, the expression on her face (right) is more than just acting - you can see the sadness in her eyes for the country they love, borne out of personal experience as well as the whole political situation for France at that time.

That scene, with the two rival anthems (bragging Germans drowned out by the gallant French) is the quintessence of the film; it has everything: romance, intrigue, heart-pounding tension, excitement, and great music. Ironically, the Nazi anthem sung by Major Strasser and his cronies (Wacht am Rheim) was actually slightly frowned upon by the Nazis - the song was more in keeping with the Teutonic spirit of the First World War, not that this really matters.

Politically speaking, the film has largely a very US-centric view on WWII (it was America's War even back then): Rick's initial apathy and cynicism, which later transforms into definite action, can be considered a microcosm for the general American perspective on the war. As he says to Sam in a moment of drunken reflection:

"It's December 1941 in Casablanca, what time is it in New York?.........I'll bet they're asleep in New York. I'll bet their asleep all over America."

As far as any other affirmative action in the war is concerned, the most the British ever get a look in merely consists of a few bumbling tourists, very much in the P.G. Wodehouse tradition of 1930's Hollywood "silly ass" aristocrats. Not even the French get a very good showing, although Renault does at least discard a bottle of Vichy water - at the very end.

Basically, America is Rick Blaine and the film bubbles up to its most exciting moments once Rick springs into action, having simmered and watched over the intrigue for the first two-thirds of the story. In an interesting ad lib, Ingrid Bergman's character immediately goes to Victor's

side when Captain Renault tries to arrest him, but Rick suddenly turns on his slimy friend, and intervenes to help Laszlo escape.

Victor's parting words to Rick again echo the sense of American interventionism:

"Welcome back to the fight. This time I know our side will win."

One considerable improvement on the original stage play is that the climax is moved from within the cafe to the exterior of the airport, where Laszlo escapes but Strasser emerges on the scene to try and stop him, until Rick decides to shoot. In an interesting bit of "Han shooting Greedo first"-style revision, Bogart originally shoots Veidt without provocation (as seen in the film's trailer), but come the final cut, this was changed to Strasser drawing his weapon first. As the French police arrive on the scene seconds later, the observant Captain Renault suddenly realises that Rick's life is in his hands, and he senses the turn of the tide:

"Round up the usual suspects."

As I've mentioned already in this blog, the good captain has all the best lines, and likewise for Louis as for Rick, there was only ever one choice for the role: Claude Rains' most famous film role was his very first one, The Invisible Man (in which he was barely seen!), but his stock-in-trade in subsequent years became smooth-talking, charismatic antagonists - perhaps the early precursor of the smooth English villain so common now in Hollywood - and the best of all his smooth operators was Captain Louis Renault. And it is Rains, who walks off with Bogart (and arguably the film) into the mist of the end titles (and a reprise of La Marseillaise), at the beginning of a beautiful friendship.

Casablanca won the Oscar for Best Picture of 1943, and was also a case of happy timing - just before the Casablanca conference between Roosevelt and Churchill, and the American invasion of North Africa that year. Not only is it therefore a great film but also marks a turning point in world history, unfurled cinematically for all time on a soundstage recreating a foggy airport runway.

It's one of those rare films that caught the mood of the time perfectly, and seems to suit whatever subsequent time or mood the viewer is in (whether upbeat or pessimistic) through its many repeated viewings, for being well made, sharply scripted, rousingly directed (by the legendary Michael Curtiz), and colourfully played by an international cast, but immortalized largely thanks to the enshrined image of Humphrey Bogart.

The mighty Stockport Plaza (complete with original organ installation) was the perfect venue for showing an old classic

like this.