Amidst all the First World War centenary commemorations this year, comparatively little but necessary due attention must be given to this classic - the war film to end all war films about the War to End All Wars. It is still as potent today as it was back in the 1930s, and almost as provocative in its message as it was then.

The greater significance is that its perspective is from the losing side (if there are any real 'winners' here.) The novel, by Erich Maria Remarque, covered a group of enthusiastic Germanic boys fired up by the onset of war in 1914 to join the cause and fight for the Kaiser. They enlist and join the fight, but life on the Front is cruel and harsh and far from the crusade they expected, but through comradeship they struggle through the battles against the French, at a price.

Particularly potent is that this was made only a short time after the Great War itself, when dark memories were starting to fade away, but Germany itself was gripped by economic depression. The country was very much in a state of upheaval, and the Weimar Repubic tried (and failed) to deal with the problem. It led to the reactionary Nazi movement in time, and the subsequent burning of copies of Remarque's most famous anti-war book.

The novel was prestigious and powerful enough for Universal studios in Hollywood, U.S.A. to acquire it for a feature film adaptation, with all the technical expertise at their disposal - and also, back in those days, a strong adherence to trench life and the environment for those young German boys on the front.

Sometimes the effect of working on such a film as this can have a profound effect on an actor; for the casting of the central role, this most definitely happened to Lew Ayres. A young romantic lead with boy-next-door looks, his casting as Paul Baumer led him to question the whole validity of warfare, just as his character does in the film. Particularly vivid is the scene where he is trapped in a shell hole in the middle of No Man's Land with a dead enemy French soldier, and realises the futility of what they are both doing in the name of their country.

It compelled Ayres enough to be declared a Conscientious Objector during World War II (although he was later allowed to join the Medical Corps - which was a similar case of life emulating art as he also played Dr. Kildare!), but his career was inevitably tarnished in the often cliquey world of Hollywood, when such attitudes during WWII were not fashionable.

Across the Atlantic, in 1930 the predictable violent reaction to the film in Nazi Germany led to sabotage and cinemas set ablaze, and pressure from Goebbels and the like to remove all "anti-German" sentiments. The subsequent sequel in 1937 The Road Back, also suffered by the political pressure imposed from Germany, and was heavily sanitised into something barely resembling the spirit of Remarque's follow-up novel. Its director, James Whale (who had directed Frankenstein and before that the British WWI play Journey's End), was never quite the same director again. It all seems highly incredible and unlikely to happen now, but recent evidence has shown how these feelings still unnecessarily come to the fore, so there are many lessons still to be learned.

My own memory of first watching All Quite on the Western Front as a child, is the unforgettable finale (not in the novel but a suitable coda) where Paul is the only one of his comrades left, and sees a small butterfly fluttering in the ground just beside his trench. Unfortunately, so too does a French sniper. When I saw this film again years later in 1991 (during 75th anniversary family commemorations of the war), a video release had inexplicably added grandiose music to the ending together with a heavily shortened edit of the film - this evidently, was one of the truncated versions of AQOTWF at the behest of the Nazis and butchered by a gullible Hollywood studio. It was only until many years later (in a restoration at the Curzon Soho), I was able to see the true, original dark ending in all its power, with no glorification, no music, just sobering respectful silence, as the sight of the soldiers looking back becomes a ghostly haunting memory.

In an era of Remembrance, here is the one war film that should be remembered most of all.

Wednesday 19 December 2018

Thursday 20 September 2018

Bill and Ted's Excellent Adventure (1988)

For the genesis of this cult, I owe a certain debt to the late night ITV American-made programme Cinematractions for being an early herald of the phenomenon of permanent teenage-inclined humour, popularised and satirised by Mike Myers in Wayne's World, but much more authentically portrayed here by Alex Winter, and Keanu Reeves.

For the genesis of this cult, I owe a certain debt to the late night ITV American-made programme Cinematractions for being an early herald of the phenomenon of permanent teenage-inclined humour, popularised and satirised by Mike Myers in Wayne's World, but much more authentically portrayed here by Alex Winter, and Keanu Reeves.This, for me, is Reeves's defining role and by far his most entertaining. He, as Edward Theodore Logan in his cheerfully non-intellectual way, is perfectly content to carry on playing noisy music and being himself, regardless of his complete lack of musical ability, or that of his chum William S. Preston - played with equal wacko gusto by Alex Winter.

There's a certain innocent charm to this generation of brainless Americans (George Washington - "the dollar bill guy" and "Born on President's Day"). Their happy ignorant bliss however is set to be torn apart due to their (not surprisingly) appalling school grades at history. Their unexpected ally in their quest to pass the subject, and save the future of their band "Wyld Stallion" (and the future of world peace!) comes from left field in the lugubrious figure of Rufus (American stand-up comedian George Carlin), sent as a time guardian from the future in a payphone booth (an obvious nod to Doctor Who's Tardis), giving Bill and Ted this device as their means to abduct various historical figures of note, in order to make this the greatest history report ever told.

The delight of this film is the unabashed way in which it allows historical figures to incorporate themselves into the lunacy without ever really compromising themselves as historical characters - Abraham Lincoln shouting "Party On Dudes!" stretches my imagination personally, but other than that I'm quite convinced by the notion of Genghis Khan rampaging through a department store full of clothes dummies, and of Beethoven jamming to Bon Jovi tunes. The one who seems to enjoy himself most is Napoleon Bonaparte (Terry Camilleri); some stock footage from Waterloo (produced by Executive Producer Dino De Laurentiis) comes in handy, before he is suddenly transported from the Austrian battlefield, and though he may not triumph at ten-pin bowling, his finest hour comes along the water slides ("Waterlubes"!) of San Dimas.

The delight of this film is the unabashed way in which it allows historical figures to incorporate themselves into the lunacy without ever really compromising themselves as historical characters - Abraham Lincoln shouting "Party On Dudes!" stretches my imagination personally, but other than that I'm quite convinced by the notion of Genghis Khan rampaging through a department store full of clothes dummies, and of Beethoven jamming to Bon Jovi tunes. The one who seems to enjoy himself most is Napoleon Bonaparte (Terry Camilleri); some stock footage from Waterloo (produced by Executive Producer Dino De Laurentiis) comes in handy, before he is suddenly transported from the Austrian battlefield, and though he may not triumph at ten-pin bowling, his finest hour comes along the water slides ("Waterlubes"!) of San Dimas.I confess, I haven't got round to seeing the sequel, Bill and Ted's Bogus Journey. Few films rarely deserve sequels (even the award-winning The Godfather Part II didn't completely pass muster.) This was however, even wackier than the original, if such a thing could be possible, with B and T dying and going into hell but having to challenge Death (just like the one in The Seventh Seal) to a game of - not chess - but Battleship, and even Twister.

I sometimes wonder if Alex Winter must be thinking: if only...?

30 years later however, Keanu Reeves may be considering going back to what he was best at.

Wednesday 14 February 2018

Shaun of the Dead (2004)

For Valentine's Day, a rather unusual form of romance - indeed the first of a whole new genre of its kind (not often repeated since): the "rom-zom-com". It's also one of the best zombie films of recent years and a pretty effective satire on the modern way of living, especially in Britain.

The "rom" element of it is represented by titular Shaun (Simon Pegg), and his struggles to keep in with his cute girlfriend Liz (Kate Ashfield): loving, but whose patience with a man like Shaun is, like for all girls, limited - especially where Shaun's geeky friend Ed (Nick Frost) is concerned. A love triangle, of sorts, between Liz and Ed for Shaun's affections.

The "zom" effect kicks into gear when the perennial meteorite - or in this case a flaming space shuttle on re-entry - flies by the Earth (by whatever method it is that turns people into zombies), and the following morning the world is the same dreary zombie-like existence outside for Shaun, except for some odd inconsistencies: the people want to walk into walls and also eat each other.

The mixture of romance with adventure works generally very well - more effectively than Titanic which mixed romance with adventure (in a "period" setting) - perhaps due to Edgar Wright's film being grounded in a believable contemporary setting.

The "rom" element of it is represented by titular Shaun (Simon Pegg), and his struggles to keep in with his cute girlfriend Liz (Kate Ashfield): loving, but whose patience with a man like Shaun is, like for all girls, limited - especially where Shaun's geeky friend Ed (Nick Frost) is concerned. A love triangle, of sorts, between Liz and Ed for Shaun's affections.

The "zom" effect kicks into gear when the perennial meteorite - or in this case a flaming space shuttle on re-entry - flies by the Earth (by whatever method it is that turns people into zombies), and the following morning the world is the same dreary zombie-like existence outside for Shaun, except for some odd inconsistencies: the people want to walk into walls and also eat each other.

The mixture of romance with adventure works generally very well - more effectively than Titanic which mixed romance with adventure (in a "period" setting) - perhaps due to Edgar Wright's film being grounded in a believable contemporary setting.

One of the film's best gags: the zombie-like passengers before the attack...

...are not terribly different to the actual zombies afterwards!

It's the first time also that I've seen the real everyday Britain as I recognise it, beyond any stereotypical American (or British) depiction. Wright weaves a skilful mixture of British comedy and archetypal zombie thriller, and his subsequent success has led him deservedly to other films of repute including Hollywood.

His cast is as exemplary as for any British film of yesterday, all seasoned actors with stage or TV experience, from veteran Penelope Wilton as Shaun's Mum, to Dylan Moran and Lucy Davis (recently to be soon in equally good comic form in Wonder Woman), and a whole score of recognisable faces, including many from British television news.

Shaun and friends, and their curiously similar fellow band of zombie battlers: Jessica Stevenson, Martin Freeman, Reece Shearsmith, Tamsin Greig, Julia Deakin, Matt Lucas.

And then there is the champion of all zombified looking British actors, Bill Nighy as Shaun's justifiably grumpy father-in-law. Nighy was already established as a familiar face from some of Britain's most entertaining recent films, and it's almost a shame that his role isn't any longer than a typical scene-stealing cameo.

And then there is the champion of all zombified looking British actors, Bill Nighy as Shaun's justifiably grumpy father-in-law. Nighy was already established as a familiar face from some of Britain's most entertaining recent films, and it's almost a shame that his role isn't any longer than a typical scene-stealing cameo.

Come the end of all this, Liz has the perfect recipe for dealing with the post-apocalypse:

"A cup of tea, then we get the Sunday [papers], head down to the Phoenix for a roast, veg out in the pub for a bit, then wander home, watch a bit of telly, go to bed."

The very last joke of the film is also delightfully satirical.

I watched and enjoyed Shaun of the Dead for the first time back in 2004 at the Odeon Colchester, and years later again on TV on holiday with my Dad. It made him laugh too, so it's a special film indeed, with its universal in the best of British humour, and also a pretty effective zombie flick.

His cast is as exemplary as for any British film of yesterday, all seasoned actors with stage or TV experience, from veteran Penelope Wilton as Shaun's Mum, to Dylan Moran and Lucy Davis (recently to be soon in equally good comic form in Wonder Woman), and a whole score of recognisable faces, including many from British television news.

Shaun and friends, and their curiously similar fellow band of zombie battlers: Jessica Stevenson, Martin Freeman, Reece Shearsmith, Tamsin Greig, Julia Deakin, Matt Lucas.

|

And then there is the champion of all zombified looking British actors, Bill Nighy as Shaun's justifiably grumpy father-in-law. Nighy was already established as a familiar face from some of Britain's most entertaining recent films, and it's almost a shame that his role isn't any longer than a typical scene-stealing cameo.

And then there is the champion of all zombified looking British actors, Bill Nighy as Shaun's justifiably grumpy father-in-law. Nighy was already established as a familiar face from some of Britain's most entertaining recent films, and it's almost a shame that his role isn't any longer than a typical scene-stealing cameo.Come the end of all this, Liz has the perfect recipe for dealing with the post-apocalypse:

"A cup of tea, then we get the Sunday [papers], head down to the Phoenix for a roast, veg out in the pub for a bit, then wander home, watch a bit of telly, go to bed."

The very last joke of the film is also delightfully satirical.

I watched and enjoyed Shaun of the Dead for the first time back in 2004 at the Odeon Colchester, and years later again on TV on holiday with my Dad. It made him laugh too, so it's a special film indeed, with its universal in the best of British humour, and also a pretty effective zombie flick.

Saturday 27 January 2018

To Be or Not To Be (1942)

For Holocaust Memorial Day this may seem a bizarre choice, but it is a highly effective riposte to Nazi tyranny and pompousness. It is also one of the most brilliant marriages of comedy and drama ever written, and all the more effective for taking place during World War II itself, in one of its darkest hours.

Was it based on an actual incident? Quite possibly, although its main conceit - of actors immersing themselves as Nazis in order to escape them - is so absurd it almost seems too ridiculous not to be true. It is also the greatest truism that actors remain actors even in real life situations.

In 1942, the war was far from over and the German Reich still far from defeated, in fact well ensconced in occupied Poland. This sublime comedy made by the master of the sly undertone, Ernst Lubitsch, told the potentially ugly story of oppression in the early stages of the war in a very carefully balanced mixture of drama and comedy, from the benefit, it should be said, of being made in a Hollywood studio in faraway USA. One of its notable producers however was Alexander Korda, himself an émigré like Lubitsch, who brought a wizened European experience to the film (as he did later with The Third Man).

For the casting of the main roles in this comedy however, Lubitsch turned to an American vintage, and found it in the wonderfully deadpan form of Jack Benny. A famous stand-up and theatrical comedian, he famously decried most of his film roles (often as part of his act), but here Lubitsch used Benny to brilliantly self-obsessive effect: as Joseph Tura, the star actor of the Lubitski Theatre in Warsaw, he knows he is the star name, not only of the theatre but also of the whole Warsaw theatre scene - at least in his eyes - but is riddled with insecurities about it, most of all from his glamorous wife Maria (Carole Lombard). Not only from the fear of her upstaging him onstage, but offstage too :

MARIA: "When I start to tell a story, you finish it. If I go on a diet you lose the weight! If I have a cold, you cough! And if we ever have a baby I'm not sure I'd be the mother."

TURA: "I'm satisfied to be the father."

His suspicion is ably exemplified in the form of Maria's circle of admirers (male of course), most especially a dashing Polish fighter pilot (Robert Stack), who sneaks out of the fourth row over to Maria's dressing room, during Tura's most famous monologue, "To be or not to be..." - much to Tura's dismay.

This running gag is one of a number of brilliant running gags that point up the farcical absurdity of human behaviour. Another is when Tura, who has already played the occupying Nazi leader in Warsaw, Colonel Ehrhardt, when dealing with the smoothly duplicitous German spy Professor Siletsky (a very convincing Stanley Ridges), has to swap places once Siletsky is out of the way and take his place, and meets the real Colonel Ehrhardt, in the form of the buffoonish looking Sig Ruman (often a memorable comedy foil for the Marx Brothers and many others), whom, to Tura's delight, uses some of the same responses and side remarks that Tura imagined he would say when he himself was playing the part: "So they call me Concentration Camp Ehrhardt!" is to be cried at many points during this film.

Tura himself is very much the leading man, around whom his dauntless supporting cast nevertheless depend. He has plenty of pretenders to this throne however besides Maria, not least Ravitch (the marvellous Lionel Atwill) who has a great stage presence but can't resist going too far and is often having to be rained in by his fellow actors. Then on the other end of the acting ladder there are Greenberg (Felix Bressart) and Bronsky (Tom Dugan), two perennially permanent spear carriers but both with acting ambitions - Bronsky gets what he thinks is the opportunity of a career, to play Hitler! His director (the excellent Charles Halton) has only cast him for a small role and is sceptical of his resemblance to the Fuehrer, but one step into the streets of Warsaw tells a very different story. It is this uncanny resemblance that proves to be the troupe's salvation - and the cause of much comedic intrigue.

Greenberg meanwhile, is the wannabe Shylock waiting for the time to come to play his great part - which he does, in ways no-one ever expected. The company stages an arrest of him attempting to assassinate Hitler (the real one), as he defends his Jewish roots:

In the process of this staged assassination attempt, the actors playing Nazis sneak onto the German transports and divert from Germany over to jolly old England. Having made their escape, a grateful British nation honours them - and most especially, Joseph Tura - with their wish to stage Shakespeare, and, you guessed it...Hamlet again. Again Tura returns to the stage to five his great soliloquy, but there are handsome servicemen up to the old tricks again...

To Be Or Not To Be is one of the best ever farces without straying too far out of its real setting. For what Casablanca did to wartime romance, To Be or Not to Be does for wartime comedy. At the time it was greeted by some as being in bad taste, which is understandable. Humour is so often a subjective experience, and I confess to certain lines that give me unease as well as the treatment of Ruman's Colonel Ehrhardt as a comedic buffoon, when the Nazis at the time were far from funny. Subsequent history however, has proven the film's point (as also with Chaplin's The Great Dictator).

Tragically, it was released after its biggest star, Carole Lombard, was killed in a plane crash on the way to meet her husband Clarke Gable. Both Gable and Hollywood took a long time to recover from the loss of one of the all-time great comediennes, but Lubitsch's film is a worthy epitaph to her glory.

Was it based on an actual incident? Quite possibly, although its main conceit - of actors immersing themselves as Nazis in order to escape them - is so absurd it almost seems too ridiculous not to be true. It is also the greatest truism that actors remain actors even in real life situations.

In 1942, the war was far from over and the German Reich still far from defeated, in fact well ensconced in occupied Poland. This sublime comedy made by the master of the sly undertone, Ernst Lubitsch, told the potentially ugly story of oppression in the early stages of the war in a very carefully balanced mixture of drama and comedy, from the benefit, it should be said, of being made in a Hollywood studio in faraway USA. One of its notable producers however was Alexander Korda, himself an émigré like Lubitsch, who brought a wizened European experience to the film (as he did later with The Third Man).

For the casting of the main roles in this comedy however, Lubitsch turned to an American vintage, and found it in the wonderfully deadpan form of Jack Benny. A famous stand-up and theatrical comedian, he famously decried most of his film roles (often as part of his act), but here Lubitsch used Benny to brilliantly self-obsessive effect: as Joseph Tura, the star actor of the Lubitski Theatre in Warsaw, he knows he is the star name, not only of the theatre but also of the whole Warsaw theatre scene - at least in his eyes - but is riddled with insecurities about it, most of all from his glamorous wife Maria (Carole Lombard). Not only from the fear of her upstaging him onstage, but offstage too :

MARIA: "When I start to tell a story, you finish it. If I go on a diet you lose the weight! If I have a cold, you cough! And if we ever have a baby I'm not sure I'd be the mother."

TURA: "I'm satisfied to be the father."

His suspicion is ably exemplified in the form of Maria's circle of admirers (male of course), most especially a dashing Polish fighter pilot (Robert Stack), who sneaks out of the fourth row over to Maria's dressing room, during Tura's most famous monologue, "To be or not to be..." - much to Tura's dismay.

This running gag is one of a number of brilliant running gags that point up the farcical absurdity of human behaviour. Another is when Tura, who has already played the occupying Nazi leader in Warsaw, Colonel Ehrhardt, when dealing with the smoothly duplicitous German spy Professor Siletsky (a very convincing Stanley Ridges), has to swap places once Siletsky is out of the way and take his place, and meets the real Colonel Ehrhardt, in the form of the buffoonish looking Sig Ruman (often a memorable comedy foil for the Marx Brothers and many others), whom, to Tura's delight, uses some of the same responses and side remarks that Tura imagined he would say when he himself was playing the part: "So they call me Concentration Camp Ehrhardt!" is to be cried at many points during this film.

Tura himself is very much the leading man, around whom his dauntless supporting cast nevertheless depend. He has plenty of pretenders to this throne however besides Maria, not least Ravitch (the marvellous Lionel Atwill) who has a great stage presence but can't resist going too far and is often having to be rained in by his fellow actors. Then on the other end of the acting ladder there are Greenberg (Felix Bressart) and Bronsky (Tom Dugan), two perennially permanent spear carriers but both with acting ambitions - Bronsky gets what he thinks is the opportunity of a career, to play Hitler! His director (the excellent Charles Halton) has only cast him for a small role and is sceptical of his resemblance to the Fuehrer, but one step into the streets of Warsaw tells a very different story. It is this uncanny resemblance that proves to be the troupe's salvation - and the cause of much comedic intrigue.

Greenberg meanwhile, is the wannabe Shylock waiting for the time to come to play his great part - which he does, in ways no-one ever expected. The company stages an arrest of him attempting to assassinate Hitler (the real one), as he defends his Jewish roots:

"What does he want from us? What does he want for Poland? Why? Why? Why? Aren't we human? have we not eyes, have we not hands, organs, senses, dimensions, affections, passions? Fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, healed by the same means, cooled and warmed by the same winter and summer? If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh? If you poison us, do we not die? If you wrong us, shall we not revenge!?"

In the process of this staged assassination attempt, the actors playing Nazis sneak onto the German transports and divert from Germany over to jolly old England. Having made their escape, a grateful British nation honours them - and most especially, Joseph Tura - with their wish to stage Shakespeare, and, you guessed it...Hamlet again. Again Tura returns to the stage to five his great soliloquy, but there are handsome servicemen up to the old tricks again...

Scottish farmers Alec Craig and James Finlayson spot a familiar place coming out of the German plane...

"First it was Hess, now HIM!"

To Be Or Not To Be is one of the best ever farces without straying too far out of its real setting. For what Casablanca did to wartime romance, To Be or Not to Be does for wartime comedy. At the time it was greeted by some as being in bad taste, which is understandable. Humour is so often a subjective experience, and I confess to certain lines that give me unease as well as the treatment of Ruman's Colonel Ehrhardt as a comedic buffoon, when the Nazis at the time were far from funny. Subsequent history however, has proven the film's point (as also with Chaplin's The Great Dictator).

Tragically, it was released after its biggest star, Carole Lombard, was killed in a plane crash on the way to meet her husband Clarke Gable. Both Gable and Hollywood took a long time to recover from the loss of one of the all-time great comediennes, but Lubitsch's film is a worthy epitaph to her glory.

Wednesday 10 January 2018

La Belle et la Bete (1946)

The recent live action Disney remake of their own animated film has reawakened interest in the old Beauty and the Beast scenario - but as that cartoon was inspired in large part by the French original, it's worth referring back to that, for it has few peers.

Certainly it is true that La Belle et la Bete reaches across to both sides of the age spectrum, as it is that rare animal, an adult fairy tale, magically directed by Jean Cocteau without sinking into heavy adult grimness, and retaining the innate beauty of the story and the setting itself

I was first introduced to Cocteau with a certain amount of caution. In the process of an experimental film we were making at Signals Media Centre Colchester with some technicians, local artists and actors, we touched on ideas of how to tell a film version of some of the classic Greek legends, such as Echo and Narcissus, as well as Orpheus in the Underworld. Such a film we watched as research: Cocteau's Orphee (above). Its quirky use of rustic and (then) modern French locations with black bikers for demonic servants and rippling water effects for mirrors was debatably entertaining, and Cocteau was feeling his way round a medium that he was only accustomed to from a distance, but was also finding new and interesting ways to express his poetry on film.

With La Belle et la Bete, made 4 years before however, he was able to find a perfect blend of mainstream story telling combined with his own poetic emotional and visual sense.

Still recognisable under an arduous make-up, is Cocteau's favourite leading man Jean Marais (who also played the title character in Orphee), who brings a classic French Gallic quality of tragic charm to the Beast. Interestingly, Marais also plays one of Belle's village admirers, which perhaps suggests (with its finale too), that a lot of what has transpired in the story may be in Belle's mind.

What's so effective about the film is that its setting outside the castle remains down-to-earth, whilst the castle remains magical and otherworldly, but the two still blend together perfectly. This is not only down to Cocteau's skill, but also I feel, the accessibility of Josette Day to play in both of these worlds so easily.

What's so effective about the film is that its setting outside the castle remains down-to-earth, whilst the castle remains magical and otherworldly, but the two still blend together perfectly. This is not only down to Cocteau's skill, but also I feel, the accessibility of Josette Day to play in both of these worlds so easily.

A weakness of the Disney version(s) was the need to have a villain, whereas in this traditional and largely faithful telling of the tale, there is a greater villain (and hero, in its way): that of Nature itself. The harshness of winter (metaphorically as well as physically) within the cold prison of the Beast's palace - it is also because of his daughter's wish for a rose that Belle's father is ensnared by the Beast in the first place, and it is also that rarely used power in blockbusters today, Love, that is the ultimate cure for both Belle and the Beast's enslavement.

But then, the French were always better expressing Love than anyone else.

Certainly it is true that La Belle et la Bete reaches across to both sides of the age spectrum, as it is that rare animal, an adult fairy tale, magically directed by Jean Cocteau without sinking into heavy adult grimness, and retaining the innate beauty of the story and the setting itself

I was first introduced to Cocteau with a certain amount of caution. In the process of an experimental film we were making at Signals Media Centre Colchester with some technicians, local artists and actors, we touched on ideas of how to tell a film version of some of the classic Greek legends, such as Echo and Narcissus, as well as Orpheus in the Underworld. Such a film we watched as research: Cocteau's Orphee (above). Its quirky use of rustic and (then) modern French locations with black bikers for demonic servants and rippling water effects for mirrors was debatably entertaining, and Cocteau was feeling his way round a medium that he was only accustomed to from a distance, but was also finding new and interesting ways to express his poetry on film.

With La Belle et la Bete, made 4 years before however, he was able to find a perfect blend of mainstream story telling combined with his own poetic emotional and visual sense.

Still recognisable under an arduous make-up, is Cocteau's favourite leading man Jean Marais (who also played the title character in Orphee), who brings a classic French Gallic quality of tragic charm to the Beast. Interestingly, Marais also plays one of Belle's village admirers, which perhaps suggests (with its finale too), that a lot of what has transpired in the story may be in Belle's mind.

What's so effective about the film is that its setting outside the castle remains down-to-earth, whilst the castle remains magical and otherworldly, but the two still blend together perfectly. This is not only down to Cocteau's skill, but also I feel, the accessibility of Josette Day to play in both of these worlds so easily.

What's so effective about the film is that its setting outside the castle remains down-to-earth, whilst the castle remains magical and otherworldly, but the two still blend together perfectly. This is not only down to Cocteau's skill, but also I feel, the accessibility of Josette Day to play in both of these worlds so easily.A weakness of the Disney version(s) was the need to have a villain, whereas in this traditional and largely faithful telling of the tale, there is a greater villain (and hero, in its way): that of Nature itself. The harshness of winter (metaphorically as well as physically) within the cold prison of the Beast's palace - it is also because of his daughter's wish for a rose that Belle's father is ensnared by the Beast in the first place, and it is also that rarely used power in blockbusters today, Love, that is the ultimate cure for both Belle and the Beast's enslavement.

But then, the French were always better expressing Love than anyone else.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

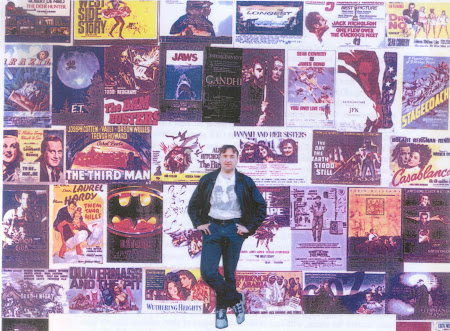

100 Favourite Films