With Kafka therefore, Soderbergh was playing an equally dangerous game in taking something entirely removed from the style of his first film: a paranoia thriller in black and white, no less, in 1991. Up until then, only The Elephant Man in 1980 or Coppola's Rummble Fish in 1983, or other relatively obscure, arty films had dared to do this since the process became largely obsolete in the mid 1960s. In fairness, the only one who really managed to pull off the gimmick successfully was Steven Spielberg with Schindler's List.

Outside of commercial interests however, black and white still retains its magic and sense of mystery, particularly in a film such as this. Orson Welles once said that black and white was the only proper medium to convey the drama and the emotion of the human face: colour distracted and brought too much awareness of the pigmentation of the skin (all but his last three films were made in black and white). It is likewise, two of Orson's most famous films, The Trial and most particularly The Third Man, that served as a benchmark for Soderbergh. His cast was, likewise, a mixture of British, American and international faces, with the likes of Theresa Russell, Jeroen Krabbe, Joel Grey (almost as one critic put it, as if his MC from Cabaret was on a day job!), Armin Mueller-Stahl, Biran Glover, Ian Holm, and even veterans like Alec Guinness and Robert Flemyng lured to play supporting roles. The always treasured sight of Guinness in a film in his later career is a typically unexpected one from him (as the Chief Clerk), but full of wry, quiet humour amid suppressed menace in his two scenes with Kafka.

In the title role, Soderbergh only ever had one actor in mind: the tall but otherwise similarly slim, gawky and nervously handsome Jeremy Irons, who brings an intelligent yet clumsy and nervous tension to the role and the decaying, uncertain Bohemian atmosphere around him.

It is not a biopic of Kafka as such, but a semi-fantasy drama incorporating elements of Kafka's life and the settings of some of his stories (most particularly The Trial and The Castle).

Things start to get creepy in the castle when the film suddenly switches over from mundane, atmospheric black-and-white, to in-your-face 'literal' colour (a la Wizard of Oz, although Powell and Pressburger reversed the process in A Matter of Life and Death from colour to b&w).

This perhaps is ultimately the film's main failing: once the sinister Dr. Murnau (a cheeky homage to the director of Nosferatu), is revealed in the flesh, all the implied terror becomes actual, and yet in the low-key presence of the talented Ian Holm, Murnau is less of a figure of fear that a would-be hack doctor with ideas above his station. The requisite chase scene in a (fantasy) film of this kind seems routine, before things return to the mundane and more comfortable black-and-white world of everyday Prague, after the colour interlude; Kafka has seen into the dark recesses of the Castle, and is depressingly content to stay in his own environment and write his stories, which turn out to have an even more vivid imagination than reality (as expected).

As such it is neither commercial entertainment or "arthouse" character observation: for some, it falls between two stools - which accounts for its relative obscurity, and the fact that I didn't get round to seeing it at the MGM Shaftesbury Avenue until two years later in 1993! I nonetheless found it a quirky, eye-catching experience, particularly with such an interesting cast, in such an old world environment.

I was lucky enough to visit Prague itself for the first time in 2017: it is the only one of the three great cultural Bohemian cities of Eastern Europe (alongside Berlin and Vienna) to have survived the ravages of history and still remained largely intact from the 19th century. The city itself is in many ways the star of Kafka, with its old, looming statues of the Saints watching over the characters like ghosts - two key locations are, of course, the giant castle (with the imposing Sternbersky Palace), and the original (and at the time, sole) bridge over the Vltava, the King Charles Bridge (named after the monarch under whose reign the bridge was designed and constructed.)

I recently watched Sex, Lies and Videotape for a second time to appreciate its virtues as a film - but I have seen bits of Kafka constantly in the intervening decades. Such a film has that curiosity value, and it's true that a lot more can be garnered from a director's "failed" film than from many of his successes.

Things start to get creepy in the castle when the film suddenly switches over from mundane, atmospheric black-and-white, to in-your-face 'literal' colour (a la Wizard of Oz, although Powell and Pressburger reversed the process in A Matter of Life and Death from colour to b&w).

This perhaps is ultimately the film's main failing: once the sinister Dr. Murnau (a cheeky homage to the director of Nosferatu), is revealed in the flesh, all the implied terror becomes actual, and yet in the low-key presence of the talented Ian Holm, Murnau is less of a figure of fear that a would-be hack doctor with ideas above his station. The requisite chase scene in a (fantasy) film of this kind seems routine, before things return to the mundane and more comfortable black-and-white world of everyday Prague, after the colour interlude; Kafka has seen into the dark recesses of the Castle, and is depressingly content to stay in his own environment and write his stories, which turn out to have an even more vivid imagination than reality (as expected).

As such it is neither commercial entertainment or "arthouse" character observation: for some, it falls between two stools - which accounts for its relative obscurity, and the fact that I didn't get round to seeing it at the MGM Shaftesbury Avenue until two years later in 1993! I nonetheless found it a quirky, eye-catching experience, particularly with such an interesting cast, in such an old world environment.

I was lucky enough to visit Prague itself for the first time in 2017: it is the only one of the three great cultural Bohemian cities of Eastern Europe (alongside Berlin and Vienna) to have survived the ravages of history and still remained largely intact from the 19th century. The city itself is in many ways the star of Kafka, with its old, looming statues of the Saints watching over the characters like ghosts - two key locations are, of course, the giant castle (with the imposing Sternbersky Palace), and the original (and at the time, sole) bridge over the Vltava, the King Charles Bridge (named after the monarch under whose reign the bridge was designed and constructed.)

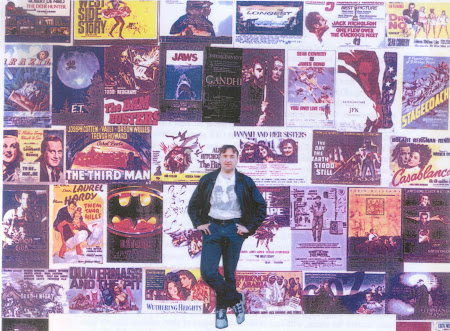

Jeremy Irons on King Charles Bridge (also below)